How a neuroscientist came to embrace the reality of acausal synchronicities

Reading | Metaphysics

![]() Laleh K. Quinn, PhD | 2023-07-02

Laleh K. Quinn, PhD | 2023-07-02

In this courageous and very personal essay, UC San Diego neuroscientist Dr. Laleh Quinn shares with us her journey from materialism to opening up to the possibility of acausal, transpersonal, mind-like organizing principles in nature. The events that led to this opening-up will amaze you. We salute Dr. Quinn for her sincerity, integrity, and commitment to truth.

In Jung’s seminal work, “Synchronicity,” he argues for a fourth organizing principle—alongside space, time, and causality—at work in the universe. As Jung experienced himself, there are some events experienced by humanity that cannot be explained on the basis of the first three principles, and thus there must be a fourth. This fourth is what Jung referred to as “synchronicity.” He defined it as an “acausal” principle, in that it did not seem to be governed by causation as normally defined within the standard scientific model.

Jung describes several instances of synchronistic experiences that could not be explained through physical causation. One of the most famous of these examples is that of the Scarab: while tending to what he refers to as an overly rational patient in his office, who had yet to break through to the deeper reality of her psyche, she related a dream she had the previous evening about a piece of jewelry in the shape of a golden scarab. Just at that moment, a scarab with green and golden hues flew into the office. Jung famously stated: “here is your scarab.” The patient was immediately lifted out of her narrow vision of the world.

This example is noteworthy, as it seems to violate what may be acceptable as normal coincidence. Coincidences happen all the time, but they vary in their probability of occurrence. What lies at the heart of Jung’s insistence that at least some coincidences cannot be explained by mere chance is a seeming violation of such probabilities. It may be a coincidence that my friend and I both decide to wear red shirts and dark jeans on the same day; however, discussing a dream of a golden scarab and immediately witnessing the appearance of a golden scarab—especially if those appearances are extremely rare, as they were in Jung’s environment—seems to point to another level of ‘coincidence.’ For Jung, these are the true synchronicities. There is something in this conjoining of events that goes far beyond our normal understanding of the way the universe works; far beyond normal chance occurrences governed by the laws of physical causation. After all, the discussion of a dream certainly did not cause the scarab to arrive at the window. Moreover, this synchronicity was a highly meaningful one for the patient.

Many of us have had these types of extraordinary experiences in our lives, but we tend to either pass them off as normal coincidences or, at best, delegate them as anomalies that must have a proper scientific explanation that we don’t yet comprehend. Experiences such as thinking of someone not thought of in years and having them call the next day have probably happened to most of us, but if you’re like me—at least the former me—I would have a twinge of excitement about coincidences like that and then promptly forget about them. For Jung, however, attending to such synchronicities goes far beyond feelings of excitement. To him, doing so provides us access to one of the most important forces of the universe, and to an understanding that, at the heart of everything, is meaning. As he states in “The interpretation of Nature and the Psyche,”

Synchronicity … means the simultaneous occurrence of a certain psychic state with one or more external events which appear as meaningful parallels to the momentary subjective state. ( p. 36)

To get to this place of understanding the meaning that underlies reality, we need to somehow overcome the natural bias we have when it comes to belief in an acausal principle. For a lot of us, including myself for most of my adult life, I would not have taken the scarab incident to prove anything mystical or meaningful. I, like many others, would maybe find it initially fascinating and interesting, but then would return to normal life; a kind of mental sweeping it under the rug. Somehow that’s easier than having to accept a new worldview. But, for Jung, sweeping it under the rug and returning to a comfortable normalcy entails missing the entire point of existence.

So, how can we better have access to the level of meaning that true synchronicities are capable of providing us? How can we get past the skeptical blocks that are our natural tendency? For me, as a neuroscientist steeped in the scientific method and rational materialism, it has been a difficult road. It took a deep personal tragedy for me to begin to experience and pay attention to the immense significance of synchronicities, and to come to have faith in their legitimacy. If I hadn’t had the personal experiences I had, I would most likely still be lacking in that faith.

Soon after my best friend and colleague of twenty years died, I began having very unusual experiences that made me suspect that he was somehow still around me. As a skeptic with lingering distrust of people who claim to be able to talk to the dead, this was—to put it mildly—out of my comfort zone. And yet, I was extremely curious. Could he really still be here in some way? I began to perform my own experiments to prove to myself he was. This was accomplished in a few ways. One was to ask him, upon waking up in the morning, for images in my mind that I would encounter later in the day. The first time I did this I saw an image of an old Wright Brothers plane. When I went running later that morning, I looked up at the rooftop of a house I had run past many times and there, attached to the roof, was a small replica of exactly that type of plane. While this was impressive, I was still able to question whether the information came from him. Maybe I’d subconsciously seen that plane but forgot, and I put that image in my mind myself. I had other experiences like this one but I was still not convinced. To be more sure, I tried a different method: asking for specific signs from him to let me know he was still here.

I was overwhelmed by the response. There were so many shocking moments where I would ask for something particular to be placed in front of me and I would receive it. Still I was hesitant to shake my materialist way of understanding the world. But one chain of signs I received finally resulted in the relaxation of my logical mind and allowed myself to jettison the last vestiges of doubt: I was driving north from San Diego to the Bay Area to visit my father in hospice. While on the highway, I asked my dead colleague to send me a sign that he was around me. I told him it didn’t matter what the sign was, just something I would understand.

Just after I asked, I heard some clicking sounds, then the song “Hello it’s Me” came on the radio. That jarred me. Was he saying hello? I wasn’t sure. Needing more evidence, I asked for further signs. Just then a car passed me with a license plate that said Camelot on it, where instead of the ‘e’ there was a heart. This was actually very significant to me for two reasons. First, I knew that Camelot was associated with King Arthur. This reminded me of the nickname (Wort) that my father—who loved the Arthurian Legends—gave me, which was the nickname Merlin gave King Arthur when he was a child. And second, it also reminded me of the last time I had visited my colleague and he took me to his favorite baking shop, “King Arthur’s flour.” This was all deeply meaningful to me, but I wanted yet more proof. So to clinch it, I asked him out loud, “if that was you I want the next song on the radio to have the word ‘knight’ in it.” Amusingly, in my mind I was thinking of the song “ Knights in white Satin,” (amusing because later I came to know it isn’t “Knights” but “Nights” in white satin). So there I was, waiting for “Nights in white satin” to miraculously play on the radio, but it didn’t happen. Instead, the very next song that came on was a song by Neil Young that I hadn’t heard for many years, called “After the Gold Rush.” As soon as it started playing, I had a chill and a knowing: the first line of the song is “Well, I dreamed I saw the knights in armor coming sayin’ something about a queen.”

I can’t describe the feeling I had at that moment; that absolute thrill of discovery and understanding; the sense of expansion and excitement. This was not something I could ignore or deny or sweep under the rug. More came, but it felt like icing on the cake. I passed two trucks on the way that were “Knight Transportation” trucks. Then, when I arrived at my family home, two books were placed facing out on the bookcase of the room I was sleeping in: both had “Knight” in the title. Next to those two books, also facing out, was Richard Feynman’s book “The Meaning of it All.” At that point I was floating, somewhere between our world and theirs, feeling the magic and wonder I didn’t allow myself to previously feel. No amount of rationalization could penetrate this new knowledge. The probability of these chains of signs—and the specificity of the signs after having asked for them—being due to mere coincidence was astronomically low. As a scientist utilizing statistical methods to show the likelihood of hypotheses, I knew the likelihood that what occurred was due to normal causation was at least one in a trillion. Most likely much, much more improbable than that. And as a good scientist should, I accepted that my working hypothesis that my colleague was sending me a message, indicating he was still somehow ‘here,’ was validated.

I consider these types of experiences to be the epitome of synchronicity, as Jung would have us understand it. Not only the improbability of this chain of events, but the deep meaning behind them, both with respect to my deceased friend and my soon to be deceased father, was profound. But I also understand that anecdotal evidence is very hard to accept. I wouldn’t have accepted it if it hadn’t happened to me. The implications are too great, if wrong. It opens up the possibility of there being a universe that is not governed by rational laws as we know them. It opens up the possibility of parapsychological phenomena being true.I deeply understand the implications of allowing oneself to open to a vast, seemingly nonsensical reality. It’s as if the floor has been taken out from under us, everything we used to ‘know’ thrown aside. But I came to understand that this can also be a great opportunity; an opportunity to willingly suspend our disbelief for a moment and consider the other possibilities, and whether those possibilities are worth the risk involved. There appears to be a choice here that we should be considering prior to dismissing Jung’s principle out of hand.

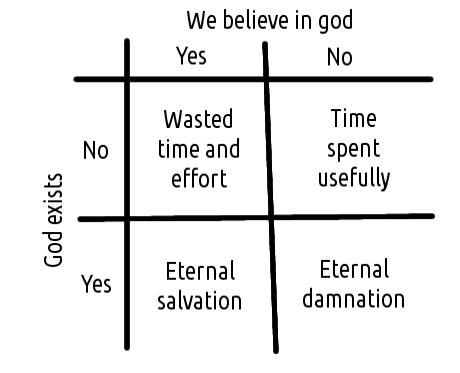

Is there a way to help with making this choice? Blaise Pascal, a brilliant French mathematician and catholic writer living in the 17th century, grappled with how to make belief in God a rational choice. When I first started studying philosophy, I was taught about Pascal’s famous wager. This intrigued me, as I was brought up in a religious household but rejected organized religion from a very early age, feeling even then that ‘faith’ wasn’t good enough a reason to believe in something. Pascal provided a kind of calculus, or cost benefit analysis, in addition to faith to help those who require more. He provided a matrix of possibilities having to do with belief in God, and asked us to consider these four options: (1) God either exists or (2) doesn’t. And we either (3) believe in God or (4) don’t believe. The ramifications of the options, according to Pascal, are shown in the table below.

Here it seems clear that the ‘rational’ choice is to believe in God, whether or not God exists. Weighing the pros and cons, the decision became obvious to Pascal. Some wasted time and effort is not worth eternal damnation. While Pascal’s wager had a definite fearsome catholic spin, and may not seem applicable to many of us, we can still use it as a way to delineate the possible scenarios under our purpose of belief in Jungian acausal synchronicities. Assume our decision matrix consists of the following: (1) synchronicities exist, (2) synchronicities don’t exist, (3) we believe in them, and (4) we don’t believe in them. How might we fill in our matrix?

First, there is the situation where we believe in sychronicities but they don’t exist. What is the cost of believing that ‘coincidences’ are meaningful when in fact they are not? This may lead to a life of succumbing to some form of magical thinking when there is no magic. We may suffer ridicule from our peers, or worse, from ourselves. This is the situation that, as an academic, I used to be very fearful of. Belief in something ‘nonsensical,’ or ‘irrational,’ may indicate that I’m less intelligent than my peers, or at best mentally unstable, which for many academics is to be preferred over lack of intelligence. Many great thinkers, even Jung himself, struggled with the fear of irrationality.

Now, what happens if synchronicities don’t exist and we don’t believe in them? We may have a sense of being vindicated, knowing we haven’t been gullible and have correctly adhered to a rational state of mind.

But let’s assume synchronicities exist and we do believe in them. This could lead to a deep understanding of reality where we have tapped into something beautiful and meaningful, providing our lives with a depth of knowledge and understanding we couldn’t have otherwise.

Finally, if synchronicities exist and we don’t believe in them, this may result in our having lost access to the true meaning of our lives.

It’s one thing to be told that the rational choice is to believe in something; it’s another thing to actually believe it even if you want to. When asked how one is to make oneself believe if they don’t already, Pascal’s advice was to fake it at first. Spend time with religious people, pray to God, act as if it’s true and ultimately it will become second nature. Perhaps we can take his advice and ‘fake’ it at first, and see what happens. One way to get started is to begin to properly research and do experiments of your own, like I did. Understand that dismissal of a hypothesis out of hand is anti-scientific. If you really want to know the truth, some dedication to rigorous research on the topic is required.

It’s ironic how many materialist scientists have not actually researched the ideas that they are lambasting. Hypotheses concerning acausal phenomena such as synchronicity, ESP, telepathy, mediumship, psychic abilities of any sort, for this type of person, are not worthy of proper analysis. They are not worth analysis at all. To them, they are wrong, a priori. As a scientist, I find this unacceptable if we are truly searching for truth. So jump in and at least make an attempt at discovery, even if it’s difficult at first. Addressing the possibility of synchronicities in a logical, rational way might just lead you to discovering they exist and, thus, provide you with the beginnings of a much more meaningful existence. Open your eyes and mind to a new understanding and see what Jung understood, that “synchronicity is an ever present reality for those who have eyes to see.”

Essentia Foundation communicates, in an accessible but rigorous manner, the latest results in science and philosophy that point to the mental nature of reality. We are committed to strict, academic-level curation of the material we publish.

Recently published

Reading

Essays

Seeing

Videos

Let us build the future of our culture together

Essentia Foundation is a registered non-profit committed to making its content as accessible as possible. Therefore, we depend on contributions from people like you to continue to do our work. There are many ways to contribute.