The Fall into the phenomenal: How idealism can help the Creation story converge with deep scientific truth

Reading | Theology

![]() Androu Arsanious, BS, MBA | 2024-02-18

Androu Arsanious, BS, MBA | 2024-02-18

Taking a clue from Christian theologian and philosopher Origen of Alexandria, Androu Arsanious argues that the biblical Fall is the story of humanity’s mistaking of the Kantian phenomena (the world as represented in perception) for the Kantian noumena (the world as it is in itself); that is, the story of our mistaking appearances for reality. Understanding this allows us to complete the Augustinian project of reconciling the stories of religion, which describe what is beyond the world in terms of the world, with the stories of science, which describe the world in terms of what is beyond the world, such as mathematical abstractions. This is a fascinating essay.

The Church bells tolled, and I felt it in my bones.

I grew up in a religious household. We’d attend church twice or thrice weekly: sports, youth group, and Sunday school. Every Easter liturgy, they’d ring the Church bells at 10:30 pm to mark the Resurrection of Christ. Incense filled the Nave as deacons sang at the top of their voices, and then we’d process around the packed church three times, holding crosses and icons. It was a surreal experience for 10-year-old me. We didn’t just accept the stories propositionally, we performed them. That’s because religious stories describe what is beyond the world in terms of the world. Good stories aren’t just heard or read. They’re felt.

Scientists tell stories too. They call them theories. Like any good story, a valid theory doesn’t just describe the past but helps us understand the present and prepare for the future. The most foundational theories in science use mathematics, a language that wasn’t invented as much as it was discovered. After all, math will remain true well beyond the heat death of the universe. As such, scientific theories are religious stories turned inside out because they describe the world in terms that are beyond the world.

No one tried harmonizing theory and story more than St. Augustine. Born in the 4th century, the Berber Bishop was a prodigal son of the Church. Raised by a Christian mother, he rejected religion as fictional absurdities in his youth and chose to walk “the streets of Babylon, in whose filth I was rolled, as if in cinnamon and precious ointments.” After moving to Italy for a teaching post, he discovered the teachings of St. Ambrose of Milan, whose biblical exegesis gave him a new purchase on his mother’s faith. St. Augustine recounts the moment he converted “under a certain fig tree, giving free course to my tears, and the streams of my eyes gushed out.” He felt a story and was reborn a saint.

A towering figure in Western thinking, St. Augustine emphasized the oneness of Truth as revealed in the Book of Scripture and the Book of Nature. He urges the faithful to “let the Bible be a book for you so that you may hear it. Let the sphere of the world be also a book for you. So that you may see it”. For St. Augustine, perception and interpretation had to be guided by rationality and revelation. In the Venn Diagram of religious stories and scientific theories, the most profound truths lay in the area that encircled both.

In the 1600 years since his death, the Book of Nature has seen a few updates. Today, it is full of theories spanning biology and physics that would be foreign to the North African Saint. Is the Augustinian project redeemable, or has the plot in the Book of Nature hopelessly strayed from that of the Book of Scripture?

The Paradox of Perception

If there were an opening chapter in the Book of Nature, it would be on Evolution. The Darwinian theory has much to say about human perceptions. Different life forms evolved diverse ways of sensing and responding to their respective environments. Bats use sound to see. Bees see UV light to sniff out their flowers. Nematodes don’t “see” but “sniff” out sugar using chemical receptors on the surface of their body. Life is the process of figuring out how to live, perceive, and respond to the environment through the senses.

Life forms use short stories—cheat codes—to survive. Male jewel beetles track their female mates using the cheat code ‘smooth, glossy surfaces = female’ to find mates. Yet, when humans started throwing out their shiny, glossy beer bottles, the male beetles started getting funky with the empty beer bottles. It nearly drove the species to extinction.

Natural selection hadn’t ‘cared’ whether the smooth, glossy surfaces were females. The cheat code had been sufficiently reliable to help the males pass their genes onto the next generation. None of the beetles needed to understand the game; they just needed to learn how to cheat.

What about our perceptual senses?

We can answer this question with mathematical precision. In evolution, game theory predicts how a population changes over time if competing for limited resources and—importantly for our purposes—how its sensory systems would have to evolve to compete effectively. A population is more likely to outcompete another population if its sensory systems are superior. But there’s a trade-off. A population can’t have the perfect cheat codes while also being attuned to the objective world. In the words of Donald Hoffman, “In evolution, where the race is often to the swift, a quick and dirty category can easily trump one more complex and veridical.”

Perceptions do not provide a window into the objective world if natural selection is valid. Instead, they’ve evolved to interfaces that maximize our fitness. Critically, the Interface Theory of Perception posits that this interface diverges from Reality.

Think of the relationship between a computer screen and its motherboard. Screens are helpful insofar as they help us manipulate electrons to ‘increase our fitness.’ Fitness in this context could mean completing a bank transaction or writing an essay. The pixels on our screen tell us nearly nothing about the nature of the motherboard. They’re not designed to help us ‘understand’ semiconductors.

Theoretically, you could open the back of your computer to tinker around with the switches in the semiconductors to write an essay or send a bank transfer, ignoring the ‘illusion’ of icons on a screen. But this red pill is a hard one to swallow. Even though screens tell you nearly nothing about how the computer works, they’re virtually essential to any task.

Likewise, our screen of perception maximizes our ability to get things done, yet conveys precisely nothing about the nature of the world. That isn’t to say we shouldn’t take what we see seriously. Walk in front of a bus, and you might not walk again. Drag that Word Document icon into your screen’s trash bin, and you will lose all your hard work. Bernardo Kastrup goes at length to stress how our perceptions don’t tell us what the world is, only how it behaves. Scientific theory quantifies these behaviors.

The ‘Fitness Beats Truth’ theory illustrates a wider conflict between real truth and desired outcomes that isn’t exclusive to evolutionary biology. Social media is a distortion field that warps online personas to maximize the shareability or likeability of their content, regardless of its underlying truth or authenticity. How often have people lied to move ahead in their careers or fibbed about their physical height to up their profile on a dating app? Consider the psychological aspects of playing sports, where pure skill and athleticism may not be enough to win a match. Or the art of the bluff in poker. Behaviors that maximize fitness are more valuable yet less veridical. Systems often disincentivize ‘truthful’ behavior.

If natural selection is true, then objects in space-time don’t have stand-alone existence in the way we think they do. Instead, our senses build an interface, a story that allows us to organize our lives. This odd conclusion is one physicists have likewise converged on.

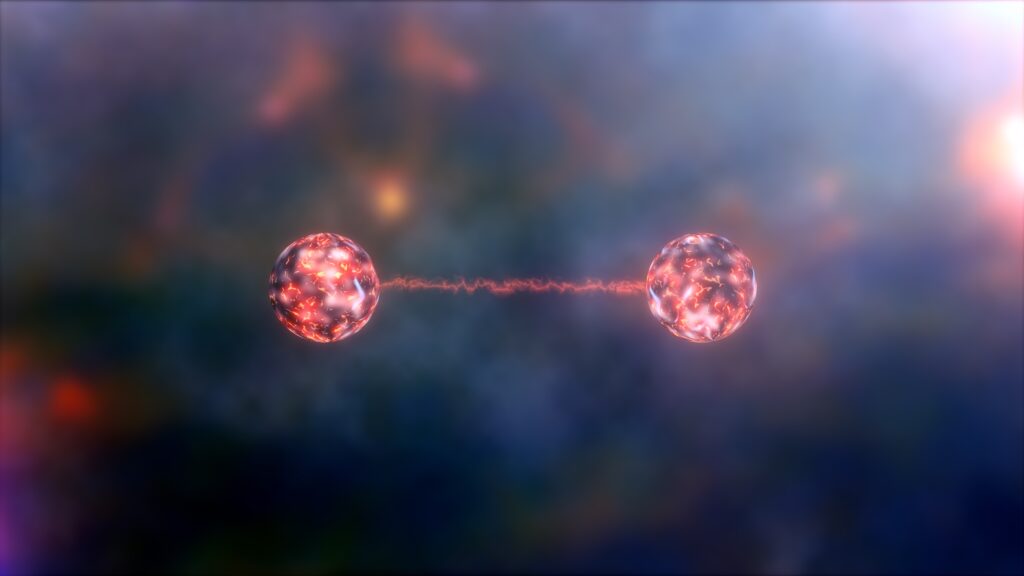

On the quantum level, energy and matter are pixelated or ‘quantized’ as discrete bits. These quantized chunks behave in ways that defy all commonsense notions of spacetime. They influence each other’s behavior instantaneously, seemingly defying both Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and our commonsense intuitions of the world. Quantum objects exist in a superposition of states, and only take on defined characteristics once measured. Such irreconcilable differences have forced many physicists to explore alternative models for understanding the cosmos.

In other words, at a fundamental level in physics and biology, our best scientific theories conclude that Reality is not what we experience it to be. Yet, because we logically cannot experience the un-experienceable, we cannot experience Reality as it truly is.

Philosophers were onto this idea centuries ago. Writing 2,500 years ago, Plato analogized the human relationship with Reality to prisoners chained in a cave, mistaking the silhouettes and shadows on its walls for Reality. To the Greek philosopher, the physical world is an illusion we can only break out of through contemplation. Immanuel Kant distinguished between the noumenal, things in themselves, and the phenomenal, things as they appear. The German philosopher proposed that, while the phenomenal world operates via cause and effect, the Noumenal world is the arena for human agency, will, and spirit. This dualistic framework for understanding our relationship with the cosmos is central to religious stories, as we will soon see.

Screens glitch and this Interface is no different. It is in these glitchy moments that we can appreciate this metaphor.

The Apocryphal Sciences

For the better part of 150 years, scientists have documented psi phenomena. Everything we think we know is confounded by psi, which include precognition, paranormal experiences, near-death experiences, and miracles. Psi phenomena are important “because they provide examples of human behavioral capacities that seem extremely difficult or impossible to account for in terms of presently recognized computational, biological, or physical principles.” There is an overwhelming amount of empirical evidence documented across thousands of cases.

Take the curious case of “The Twins,” described by famous neuroscientist Oliver Sacks in the 1970s. The two brothers couldn’t perform basic arithmetic calculations and had been institutionalized for the better part of 20 years, being “variously diagnosed as autistic, psychotic, or severely retarded.” However, during one consult, Sacks found them riffing prime numbers to each other, sometimes over 20 digits long. This would’ve been an impossible feat for the most powerful computer at the time, let alone for anyone without arithmetic skills.

There are documented reports of people who can be hypnotized into thinking their skin is burning, only to have their skin spontaneously blister shortly afterward. Then there are apparitions and documented cases suggesting premonitions of death. Near-death experiences have turned skeptics into advocates for alternatives to conventional materialism. Faith healing cases defy conventional explanations. Inert substances with no clinical effects can ‘elicit’ a state of mind that instills positive clinical effects.

The glitches happen constantly, yet the scientific theories we tell ourselves simply cannot explain this data away. But religion might…

The Fall into Evolution

With each page turn in the Book of Nature, the world has gotten stranger. Evolution and physics conclude that the world as we experience it is not the world as it truly is, and psi breakout experiences appear to vindicate this claim.

It is here where religious stories pick up the mantle. Recall that religious stories describe what is beyond the world in terms of the world. We’ll enlist the help of the third-century Church Father Origen of Alexandria to guide our brief tour. A pioneer of Biblical exegesis, it is on Origen’s shoulders that Augustine stood when he proclaimed the oneness of Truth. Origen comes as close to recognizing the duality of the created order—in terms of the noumenal and the phenomenal—as the most viable interpretation of the Judeo-Christian Creation account in Genesis.

Origen notes this in his commentary on Genesis 1:6, when God creates the firmament or sky. That God first creates the light and darkness on Day 1, then the sky on Day 2, suggested to Origen the need for an alternative, allegorical interpretation. He writes, “The first heaven … which we said is spiritual, is our mind, which is also itself spirit … sees and perceives God. But that corporeal heaven called the firmament is our outer man, which looks at things in a corporeal way.” For Origen, God created a spiritual and ‘corporeal,’ or physical, world.

At the end of the first chapter, God crowns his creation, with humans famously formed in His image and likeness. But not the material image, writes Origen: “For the form of the body does not contain the image of God, nor is the corporeal man said to be ‘made,’ but ‘formed.’”

In Genesis 2, God creates man in his Image by molding a “wet clod” of soil and blasting his breath into it. Humans have a unique relationship with their Creator, according to Origen, who observes that “it is our inner man, invisible, incorporeal, incorruptible, and immortal, which is made according to the image of God … But if anyone supposes that this man … is made of flesh, he will appear to represent God himself as made of flesh and in human form. It is most clearly impious to think this about God.”

Why does Origen think God needed to create a corporeal and spiritual world?

God places him in Paradise, the Garden of Eden. The root word for garden is “ganan” in Hebrew, which means “to defend, cover, or surround.” In every other use, it describes the defense of a city, as if in battle. God then creates a helper, often better translated as a ‘rescuer’: a woman from the Man’s rib who lives in shameless nudity with the Man.

Among the shrubbery of the Garden are the Tree of Knowledge and the Tree of Life. God explicitly tells the couple not to eat the former’s fruit lest they “surely die.” Here, we see a hint of the trade-off between having the ‘cheat codes’ to knowledge, courtesy of the first tree, and participating in everlasting life, courtesy of the second tree.

A Serpent resides in Eden. It asks the Woman what God had commanded for the Tree of Knowledge, and she responds by saying God told them not to eat or touch its fruit. By adding to God’s words, Eve opens the door for the Serpent to twist God’s words further. He replies that, to the contrary, her eyes would be opened and that she and her husband would become gods.

Serpents play an evolutionary role in our history, for only creatures with acute vision and quick reflexes could avoid the tree-dwelling reptiles. Sure enough, the serpent’s words opened her mind, and she “took of its fruit and ate.”

But in their attempt to raise their consciousness, the fated couple is brought lower than the dirt. The “original sin” is one that all humanity partakes in, and for Origen, the events precipitate a fall of humanity into the safety net of the corporeal order. Adam and Eve’s eyes opened to the material realities that would forever consume their descendants. God had anticipated this fall and engineered the corporeal world to accommodate their eventual self-destruction. This, for Origen, is why God created the corporeal world.

The fall sparks a sense of self-awareness that sheds light on the couple’s corporeal vulnerability. The Tree of Knowledge opens their eyes up to the possibility of death. Overcome with fear, Adam and his wife cover themselves in fig leaves and fearfully cower as though hunted like wild beasts, for instinct has taken over.

In Kantian terms, the ordeal of Eden is the human fall out of the noumenal and into the phenomenal place. Adam and Eve lose the blissful truths of paradise and must now face the nasty, brutish existence awaiting them in the corporeal world. Fitness is of primary concern now. True to the Serpents’ words, their eyes ‘see’ and fall into the corporeal world, yet are also blinded to the noumenal, ‘spiritual’ place they once inhabited. Eden was cloistered and gated because the noumenal world could not be accessed from the phenomenal world. And once you fall into the phenomenal world, you cannot return to the noumenal place.

The story of the fall is, therefore, a tale of exile into Plato’s Cave. Origen writes that “this sinking results in us taking on bodies” and warns that “all rational creatures who are incorporeal and invisible, if they become negligent, gradually sink to a lower level and take to themselves bodies suitable to the regions into which they descend.”

As a result, the embodied souls of Adam and Eve become ensouled bodies. Material corporeal concerns take center stage for man, woman, and beast. Fitness is the new name of the game, and God reluctantly pronounces its accursed rules.

The Serpent will slither on its belly and, as a symbol for all animal life, enmity erupts between it and humankind, telling it that humans “shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise its heel.” The interface between humans and beasts is created.

For Eve, her toil will be in labor and the accursed state of yearning after her husband. The helper has become helpless because the corporeal world is now too dangerous for her to fend for herself. Indeed, Adam’s first act after their exile from Eden is to name his wife Eve, a ‘power move’ symbolizing the rule of man over woman. The interface between man and woman—patriarchy—is born.

Adam fairs no better, for the soil he once tilled is now cursed and must be tilled in toil. The Earth will wage war on him, using every thorn and thistle. The thing he was created from will now entomb him: “From dust you came, and to dust, ye shall return.” The interface between humanity and the cosmos boots up.

God’s parting gift is to knit tunics out of “mortal skin” for the couple. Origen observed that “heir being clothed with tunics of skins, contain a certain secret and mystical doctrine far transcending that of Plato of the souls losing its wings, and being borne downwards to the earth until it can lay hold of some stable resting-place.” The interface is sealed with mortality, and the world as we experience it is now here for good.

The Bible blossoms when stripped of materialistic presuppositions, and the Augustinian project of reconciling the Book of Nature with the Book of Scripture takes on new life. But we must abandon the idea that Reality is ontologically a physical place. As new chapters in the Book of Nature are written, we should footnote religious texts to catalog the ultimate Oneness of Truth. Only then can we synthesize and harmonize truth between science and religion.

Bibliography

- St. Augustine, Confessions Book II, Chapter 3 (8). Available at: https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/110102.htm#:~:text=Behold%20with%20what%20companions%20I,me%2C%20I%20being%20easily%20seduced. Accessed 15 Jan. 2024.

- St. Augustine, Confessions Book VIII, Chapter 12. Available at: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf101.vi.VIII.XII.html Accessed 15 Jan. 2024.

- Male Jewel Beetles. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/krulwich/2013/06/19/193493225/the-love-that-dared-not-speak-its-name-of-a-beetle-for-a-beer-bottle Accessed 15 Jan. 2024.

- Hoffman D, The Interface Theory of Perception: Natural Selection Drives Truth Perception to Swift Extinction. Available at: https://sites.socsci.uci.edu/~ddhoff/interface.pdf Accessed 15 Jan. 2024.

- Kant’s Transcendental Idealism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-transcendental-idealism/#Bib Accessed 15 Jan. 2024.

- Sacks, O. The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat. Accessed 15 Jan. 2024.

- Hallson, P. (2016). ‘Ghosts and Apparitions in Psi Research (Overview)’. Psi Encyclopedia. London: The Society for Psychical Research. <https://psi-encyclopedia.spr.ac.uk/articles/ghosts-and-apparitions-psi-research-overview>. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- All quotes from the Bible are from NKJV, available at https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis+1&version=NKJV Accessed 15 Jan. 2024.

- Origen Homilies on Genesis 1.2.

- Paulsen, David L. “Early Christian Belief in a Corporeal Deity: Origen and Augustine as Reluctant Witnesses.” The Harvard Theological Review, vol. 83, no. 2, 1990, pp. 105–16. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1509938. Accessed 15 Jan. 2024.

- Blue Letter Bible, Strong’s Reference: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h1598/kjv/wlc/0-1/

- McGrew, W.C. Snakes as hazards: modelling risk by chasing chimpanzees. Primates 56, 107–111 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-015-0456-4

- Contra Celsus Chapter 40. Available at: https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/04164.htm

Essentia Foundation communicates, in an accessible but rigorous manner, the latest results in science and philosophy that point to the mental nature of reality. We are committed to strict, academic-level curation of the material we publish.

Recently published

Reading

Essays

Seeing

Videos

Let us build the future of our culture together

Essentia Foundation is a registered non-profit committed to making its content as accessible as possible. Therefore, we depend on contributions from people like you to continue to do our work. There are many ways to contribute.