The symbiotic ecology of the psychedelic realm

Reading | Philosophy of mind

![]() Asher Walden, PhD | 2022-09-04

Asher Walden, PhD | 2022-09-04

The many seemingly autonomous entities encountered in the psychedelic realm suggest that human consciousness is the result of psychic symbiosis, entailing both personal and transpersonal formative principles, argues Dr. Walden in this fascinating essay.

Psychedelics are becoming mainstream. In the wake of cannabis legalization, and following some of its legal and economic pathways, several psychedelic plants have been decriminalized in a number of cities across the US; and beginning in 2023, psilocybin will be legal (with various restrictions) in the entire state of Oregon. Clinical research on the medicinal use of psychedelics is being pursued at a frenzied pace, fueled by both philanthropic funding and extremely promising early results for their safety and efficacy in treating various recalcitrant mental health issues including addiction, depression and PTSD. There are well-endowed centers for research at Johns Hopkins, The University of Texas at Austin, NYU, Ohio State University, Mass General Hospital, etc., as well as a number of non-profit and public benefit corporations. And of course, for-profit and publicly traded companies have invested heavily in manufacturing and standardization, not only to supply clinical research, but to gain market share in the case that psychedelics are legalized nationally—an outcome they forecast the next few years. This list is of course limited to my own country; similar movement is parallel, or even outpacing these developments, in Canada, the UK, The Netherlands and elsewhere.

The need to train mental health professionals in the optimal use of these medicines has produced a surge in published work on psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. But there is also a growing literature on the historical contexts of psychedelic plant use, the protection of indigenous knowledge and cultures, philosophical and speculative works on the content of psychedelic visions, and so on. This has opened up new possibilities for exploring psychedelics in the context of the arts, music, social theory, religious studies, and not least of all, the philosophy of consciousness. What follows is a beginning, an effort to make the first few steps in using the data from psychedelic experience to expand our philosophical understanding of what consciousness is, and how it relates to existence itself.

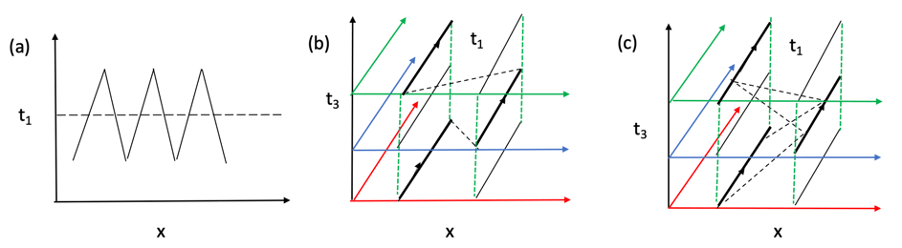

If a given consciousness is like everything else in the cosmos, we should be able to clarify at least two dimensions of its ontological structure: its distinction from other consciousnesses and its internal coherence. In other words, what is it that distinguishes a consciousness or a conscious self from other conscious selves? But also, what are the internal components or aspects of a consciousness, and how are they held together? Several authors have made good inroads into the first issue, describing in various ways how consciousness, though ultimately a single substance, can partition itself amongst selves who believe they are independent. But the issue of internal complexity has not been adequately addressed. While we may recognize certain kinds of multiplicity in our conflicting desires and discrete levels of self-knowledge, these considerations are almost always examined from a psychological perspective only, ignoring what they suggest about the metaphysics of consciousness. I would like to move in this direction by suggesting two kinds of constitutive principles: functional independence and symbiosis. Both of these principles can be understood by analogy to the human body.

By functional independence within the human body, I mean the limited integrity of the various organ systems. The circulatory system, the nervous system, and so on, each have a degree of functional autonomy, but at the same time, they are hierarchically structured in the sense that they serve a common telos [Editor’s note: purpose, goal] in the functioning of the body as a whole. Thus, they have both lateral interrelations, to the extent that they overlap, cooperate, and sometimes interfere with each other, as well as vertical relations. The overall integrity of these systems requires smooth functionality in both dimensions. In a similar way, we learn from the Abhidharma tradition [Editor’s note: ancient Buddhist philosophy] that consciousness can be analyzed in terms of its discrete perceptual bases, which have a number of interrelations. What we call sight, sound, hunger and anger are so many disparate consciousnesses that operate in parallel, but are also vertically aligned (by the five aggregates or categories) to form the experience of objects and events in the constructed world. The perceptual world is neither ultimately real, nor ultimately unreal. It simply has the constructed nature that it does, which is shared, robust and continuous in (our experience of) time. The nature of the self is that it is one construction among others. So, from this Buddhist perspective, if you want to understand what the self is, you simply need to understand the process by which the bases or foundations of perceptual consciousness are synthesized.

I have explored this kind of internal complexity in an earlier essay. For the remainder of the present essay, I want to focus on the other kind of internal plurality: namely, symbiosis. The analogy of the body, in this case, rests on the observation that much of our body is not our own at all, but made up of various quasi-independent microorganisms. I have in mind especially our gut bacteria, which are so important not only for the digestion of our food, but for the regulation of mood, our immune system, and even cognition. Researchers have found strong connections between our microbiome, stress and auto-immune responses such as inflammation, which is at the root of a host of physical illnesses. There is even evidence showing a relationship between gut biome diversity and autism. Given the sheer number of neurons in the gut, and its role in producing neurotransmitters such as serotonin, we are justified in saying that the gut thinks for itself (think, for instance, of ‘gut feelings’). But what’s important here is the fact that this second brain is, in large part, genetically alien. This means that our bodies are much more complex (logically, not just biologically) than we normally assume.

The body is like a nation-state in miniature, where most of its citizens are genetically similar, but a substantial minority are immigrants and refugees of questionable legal status. The issue of hospitality is of paramount importance here. At the risk of multiplying analogies recklessly, think about how one might respond to ants in the house. If you have a lot of ants there are at least two options. On the one hand you might lay out traps and poisons. There is even the nuclear option: the kind of poison which the ant takes back to the nest and which wipes out the entire colony. On the other hand, you could simply seal cracks in the molding and do a better job sweeping up crumbs, to minimize the motivation for ants to come in in the first place. Which option do you instinctively prefer? Now, what if I suggested that the ants you have were a special kind of carpenter ant, which actually helped maintain your house, repairing rotten wood, and even driving away disease-carrying vermin? Then you might think twice about trying to seal them out, much less trying to kill them all off. Just so, most of the bacteria in and on your body are not only not harmful, but very helpful in minimizing the harmful bacteria, along with their other household tasks. Doctors have finally started to come around to the dangers of overprescribing antibiotics! In our era, the most dangerous cells in our body are not foreign invaders, but our own cells mutated out of control in the form of cancers.

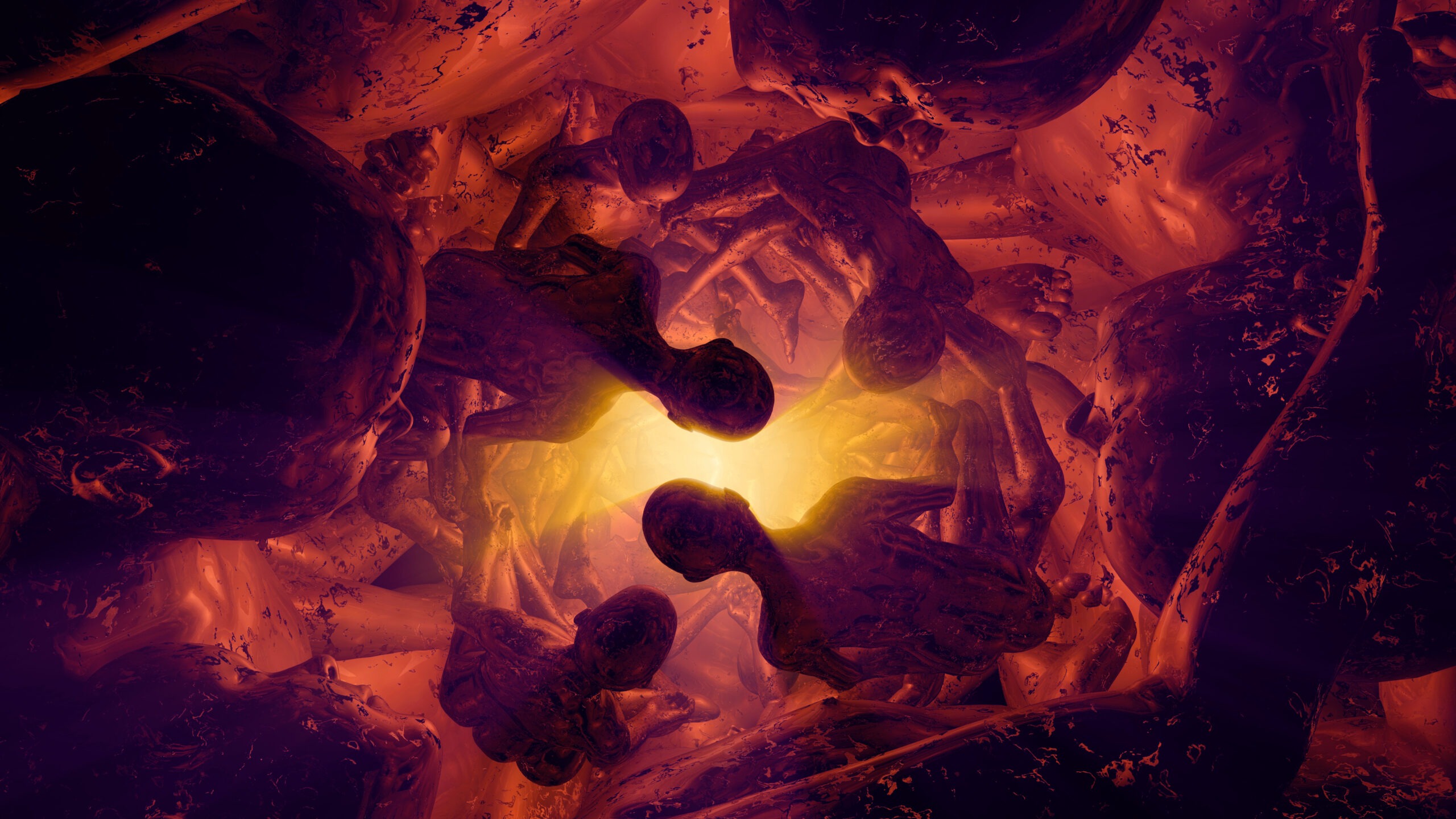

What I want to suggest here is that many of the thoughts and feelings we experience as ‘our own’ are not really our own at all, but genetically alien, quasi-independent selves, which exist in symbiosis with the ‘native’ aspects of our conscious lives as described in the Abhidharmic analysis. They are those mysterious and mischievous beings that have been called at various times gods, spirits, angels, demons, elves, archetypes, mass-delusions, aliens, neuroses, and so on. They constitute a rather heterogenous collection of forms of consciousness that have their own psychologies, their own moral principles, their own likes and dislikes. But like the microbiome in our guts, they serve prophylactic and other functional purposes that we are deeply dependent on. If we welcome them as full citizens of our psyche, we will be all the stronger for it.

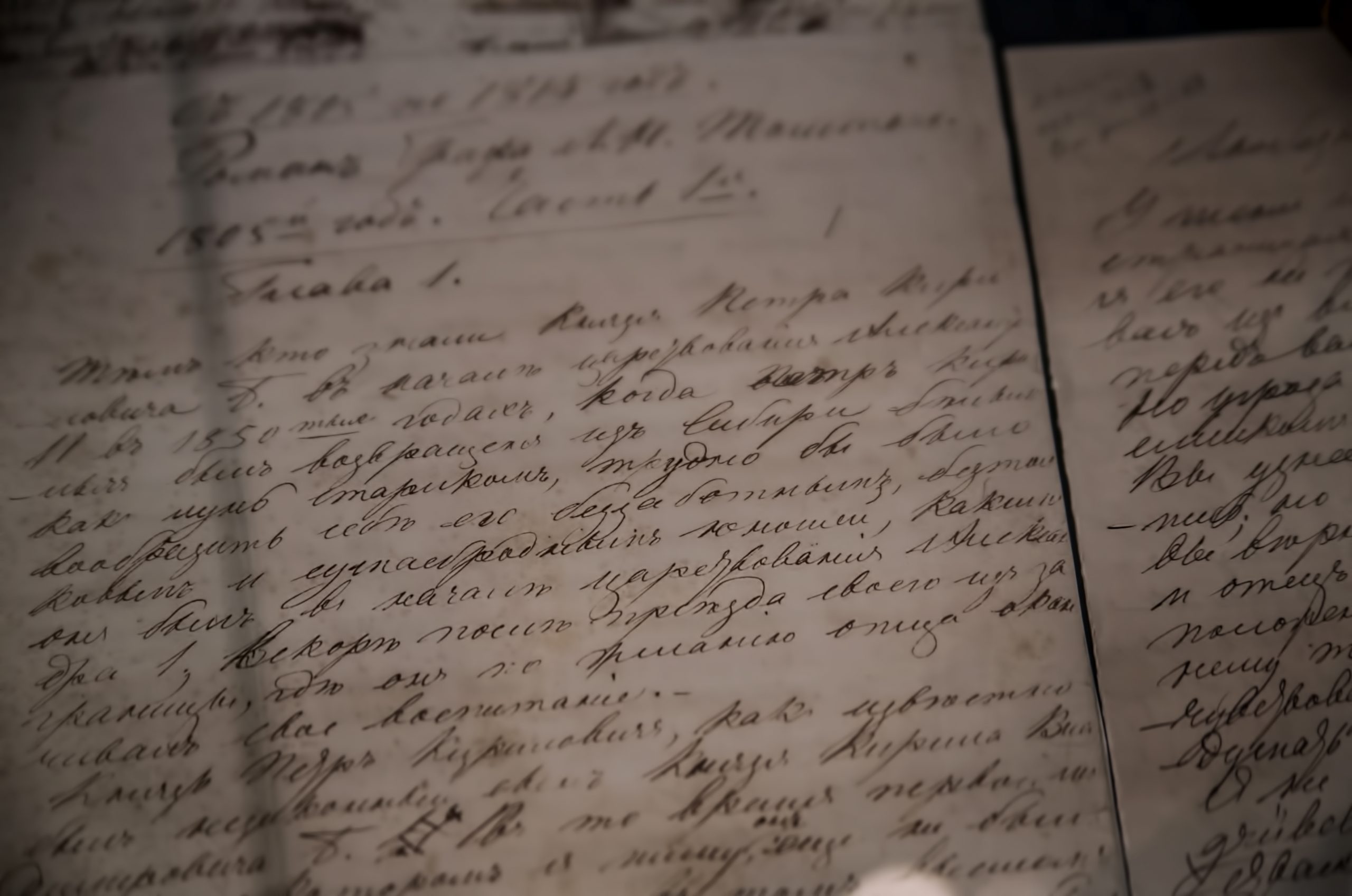

The basis for the present proposal comes from the contemporary confluence of comparative mythology and religion on the one hand, and on the other the renaissance of research on psychedelics. This convergence has its roots in the work of the patriarchs of the ‘perennial philosophy’ (William James, Huston Smith, Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts), who were themselves fascinated by the similarities between ancient myths and the phenomenological contents of non-ordinary states of consciousness. The implicit suggestion is that humans universally share the neurological capacity to enter into visionary states in which they experience interior but transpersonal events of the highest reality, value and meaning. The ways in which people enter these states are rather varied. They can be triggered by (among other things) oxygen depletion, fasting, sensory deprivation, drumming, psychoactive medicines, or most often, some combination thereof.

The contents of visionary states are widely consistent not only with each other, but with the contents of the world’s mythologies and religions. They include several classes of material experienced as ‘given’: Gods, spirits, angels and demons, and inhabitants of other realms of being; conscious intelligence in non-human actors such as animals, insects, plants and the Earth itself (herself?); Consciousness/Existence itself experienced as unified and purposeful; the souls of others, alive and dead; specific insights about one’s mortal life encompassing healing, moral renewal and vocation. So, from the perspective of the sheer subject matter, it obviously looks as if the stories, myths and beliefs that we think of as ‘religious’ may have their origin here. But what is actually happening here? Are people who take this medicine simply projecting unconsciously remembered myths and repressed wisdom onto the dreamlike stage of visionary experience? Or are the myths actually the literary record of encounters with independent non-physical realities?

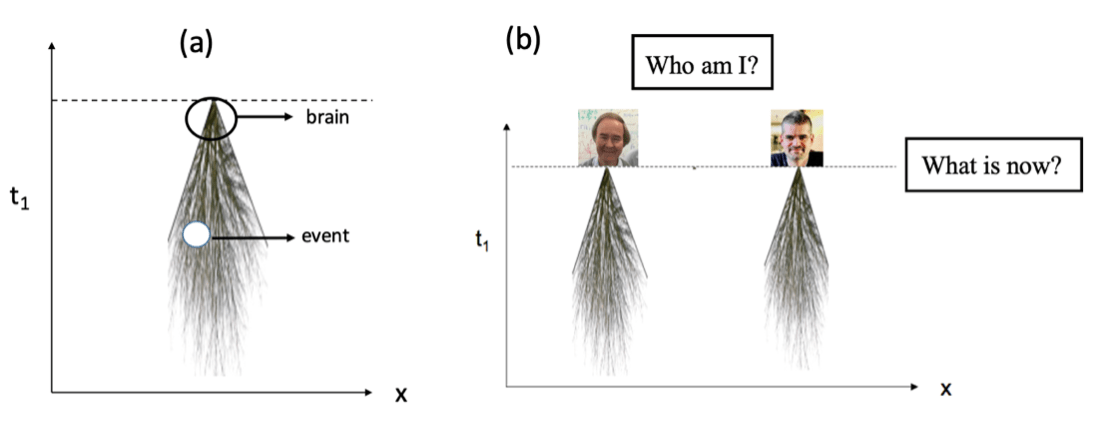

The third option, a middle way, is that the experience is literally a manifestation of mind, that is, an opportunity to see the internal structure of one’s own consciousness, and an insight into the nature of consciousness more generally. Up till now, the primary context for describing and interpreting the entities encountered in visionary states has been mythic, religious and/or supernatural. On the other hand, the common denominator in all these categories can be seen as consciousness itself: the appearance of consciousness in unexpected places, and in unexpected forms. The term ‘psychedelic’ means ‘mind-manifesting.’ I want to argue that this is precisely what is happening in these states: the structure of the personal self, the ordinary ego identity, is temporarily stripped away, or at least thinned to the point of transparency, so that the underlying structures and forces that constitute consciousness more broadly are revealed. In this case, the various beings encountered are not independent selves in the way that individual humans (think they) are; rather, they are patterns in the structure of consciousness, best understood (so far) in terms of Jungian archetypes.

Recall that Jung [Editor’s note: Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung] was essentially a Kantian at heart. He believed that the archetypes functioned as structuring principles, universal categories that gave our experience their shape and texture. But how could this possibly work? Kant was talking about space, time and logical categories. These principles structure experience by giving form, but no content, to perceptual elements. By following out Jung’s analysis, we can see that the archetypes actually contribute a different kind of structure to experience, by giving perceptions their semiotic salience, their meaning and value. For us, things like sex, warfare, hunting, pilgrimage, birth and death are to discrete individual perceptions the way the constellations are to individual stars. They provide an over-arching trajectory and form that allows us to cognize vast quantities of data in very efficient ways. The way they do that, in part, is by turning an otherwise senseless series of events into a coherent story. But the relationship goes both ways: we rely on these archetypes for sense-making, while they rely on us to give them specific content. They are interested in our lives and push us in various unconscious ways toward courses of action that tell the story that they want (us) to tell.

In order to flesh out this admittedly speculative proposal, we can address these three questions: what is the evidence that these things exist? What is their ontology or mode of being? And how does this contribute to the working out of the idealist ontology more generally? Concerning the first question, what is the evidence that psychic symbiotes exist? Simply that we seem to encounter them, repeatedly and robustly, in roughly the ways that Jung says we do: in myths, dreams and psychedelic visions that spill over into our ordinary conscious life in distinctive and persistent ways. This is not to say that the archetypes as Jung understood them are the only such psychic symbiotes that exist—there is some reason to think that there are others. And ‘archetypes’ might not be a natural kind either: the term may turn out to comprise several sets of beings that are rather different in their logic, nature and scope. But whatever the actual extension of the category of psychic symbiotes, they do share certain ontological features that we can briefly summarize.

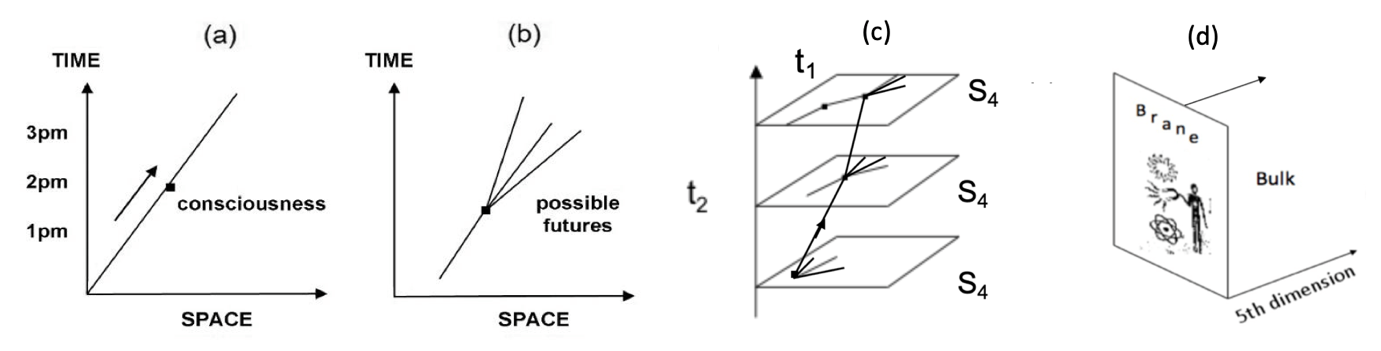

For one thing, these other beings are made up of consciousness. This should not be read in a deflationary sense, as if they are merely products of our collective imagination; after all, many of us believe that everything is, ultimately, made up of consciousness. My earlier use of the analogy to the physical body should not be taken to imply a dualist doctrine either. Nonetheless, a consciousness-only worldview, even if (or especially if) it is ultimately monistic or non-dualist, must take careful account of the deep, perhaps infinite internal complexity of consciousness, its varied forms, manifestations, resonances and conflicts. To say that those other beings are made up of consciousness is to say that they are no more or less real than our own conscious selves. However, unlike us, they do not necessarily have a bodily anchor within perceptual spacetime.

They are located both intrapsychically and transpersonally. That is, while we experience ourselves as located within, and in primary relation to, a single physical body, they appear to exist simultaneously within our own consciousness and within that of other people as well. (This is where the analogy to bacteria apparently breaks down.) On the other hand, if we change our frame of reference to look at souls as such, rather than bodies, we could just as easily see the others as unified and simple, and understand ourselves as located simultaneously within them, and between them. In fact, given the much longer timespan of their existence as compared to our own, this inside-out perspective is probably the more appropriate one.

Finally, they want what they want—we should not give in to the temptation to think that they are merely subaltern expression of ourselves. They are mostly (but not always) friendly to humans, to the extent that they depend upon us as much as we depend upon them. But their forms of life are profoundly different from our own. As to the subjective experience of their own conscious perspective, we can hardly imagine. It’s not just a matter of imagining what it would be like to be a dog or cat, instead of a human. It would be more akin to imagining what it would be like to be a gene, or a galaxy.

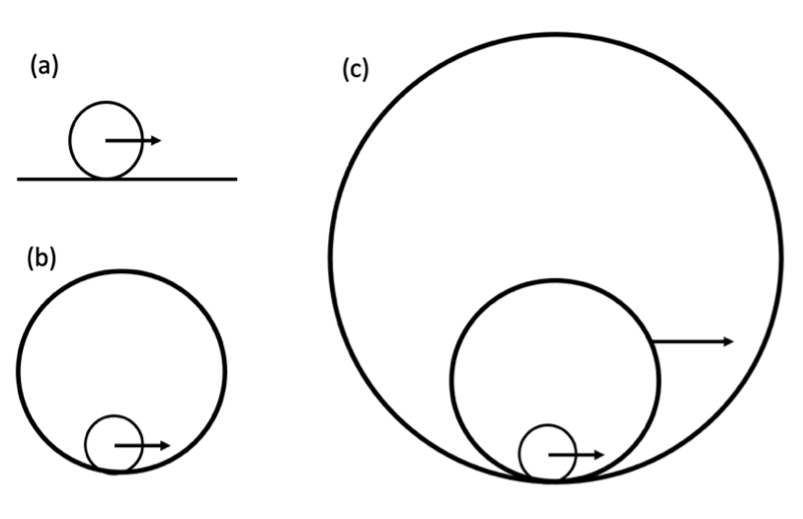

The third question asked above was, how does this kind of consideration contribute to our ongoing efforts to ramify the idealist perspective? It shows how human consciousness is simply a braid or a strand in the tapestry of consciousness that is the cosmos, where each stand is itself a tightly woven band of finer threads, and simultaneously is itself woven into larger braids. Idealist metaphysics tend to echo the neo-Platonic trajectory in treating the singleness of ultimate consciousness as primary, and its various manifestations as derived from that original unity. On the other hand, what would it look like to treat the most specific, most diverse plurality of consciousnesses as basic, with unity being generated by successive modes of interrelation? The middle way here is to allow for a flexibility of perspective, such that we can treat, for the purpose of a given analysis, any level or frame of consciousness as basic, and then move either ‘up’ or ‘down’ to look at its parts, or that of which it is a part.

Kant taught us that time, space and the elements of logic are stipulations of the way we organize perceptions in conscious experience. The upshot of this line of reasoning is to emphasize that mereology, the relationship between a whole and its parts, between the one and the many, is similarly constructed. This applies, in ways that may make us uncomfortable, to ourselves as well. It is strange to think that the parts that comprise us are not entirely homogenous, not entirely our own. And it may be even more difficult to accept that we ourselves are only parts, from the perspective of some greater whole. For a number of social and political reasons, it is salutary in our time to continue to push away from Leibnizian Monads, understood as individual discrete units of consciousness, and towards a greater sensitivity to the ways in which consciousnesses overlap, intertwine and mutually constitute one another. Likewise, we should push back against the notion that human consciousness as we normally experience it is the basis or measure for all forms of consciousness in the universe. It may be that the use of psychedelics, and the creative possibilities for culture that they may inspire, will help in this regard.

In lieu of a traditional bibliography for this informal essay, I would like to acknowledge, with gratitude, the influence of Dr. Robert Corrington in my own work.