Simple code in the mind of God

Reading | Computer Science

River Kanies | 2023-06-04

Insofar as the activity of the mind of nature can be modeled as computation, the complexity of our physical universe is an inevitable, emergent outcome of nature’s computational potentialities, even if its innate, fundamental ‘programs’—basic ‘thoughts’ in the ‘mind of God’—are extraordinarily simple. River Kanies makes this point by leveraging Stephen Wolfram’s notion of ‘ruliad.’

The core tenet of metaphysical idealism is that only consciousness exists irreducibly. It follows that all of reality is generated within, and experienced by, a universal consciousness. We may call this universal consciousness ‘God,’ provided that we avoid anthropomorphizing it. Under idealism, because anything conceivable is possible within imagination—an inherent and spontaneous activity of consciousness—instead of asking ‘what is possible in nature?’ we must, instead, ask ‘why do things seem to follow such rigid laws?’ And ‘why does God seem to be playing dice?’ (as in microscopic quantum phenomena). The purpose of this essay is to hypothesize intuitive answers to these questions, by leveraging Stephen Wolfram’s concept of the ruliad. After all, at the end of the day, it is our intuition that we act upon, not so much our beliefs; and certainly not some sort of ‘objective’ truth, which we as mere humans cannot access directly.

Wolfram defines the ruliad as

the result of following all possible computational rules in all possible ways … it’s something very universal—a kind of ultimate limit of all abstraction and generalization. And it encapsulates not only all formal possibilities but also everything about our physical universe—and everything we experience can be thought of as sampling that part of the ruliad that corresponds to our particular way of perceiving and interpreting the universe.

As such, insofar as we can model the universe as a computational system, the ruliad is the maximum expression of its potentialities.

If we go back to the ‘beginning of the universe’ from the perspective of idealism, we start with the mind of God in the form of infinite untapped potential. We can conceive of the nascent God-mind imagining at whim, no holds barred. Then, at some point, God becomes interested in creating a (computational) structure within which realities can be constructed. There is still infinite potential, but now there are constraints at least within this ‘slice’ of the activity of the God-mind. In a sense, we could say that the idea of computation itself is a sort of structure, or a class of structures (there can be different types of computation, but they all have structure and constraints). If we accept Wolfram’s claim that the ruliad is an “inevitable” formal construct that follows directly from the existence of computation, and must therefore “necessarily exist” (as a concept in the mind of God, let’s say), then as soon as God decides to create a structure, that structure is the a nascent version of the ruliad by default: the collection of all possible computations run on all possible states.

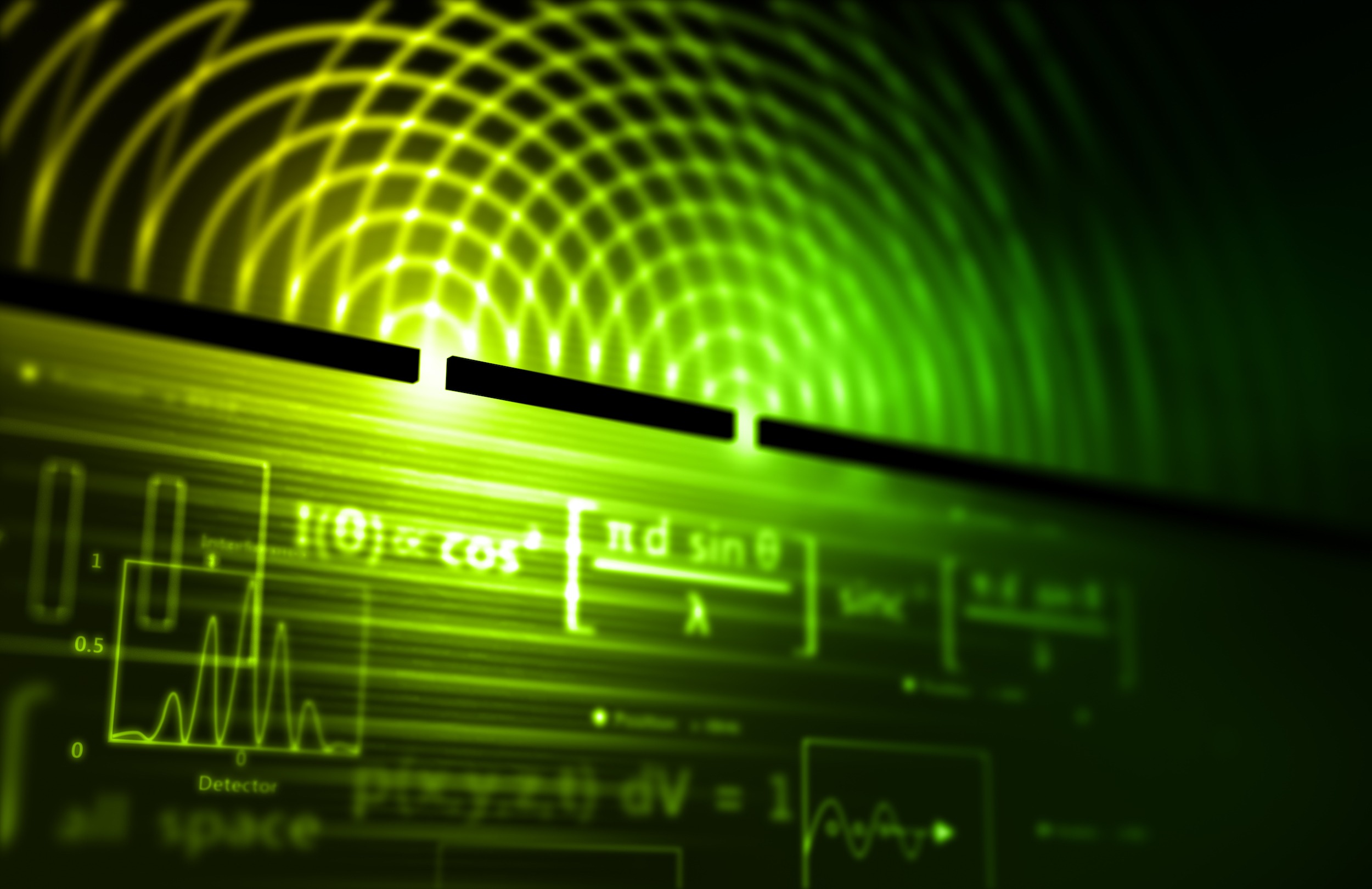

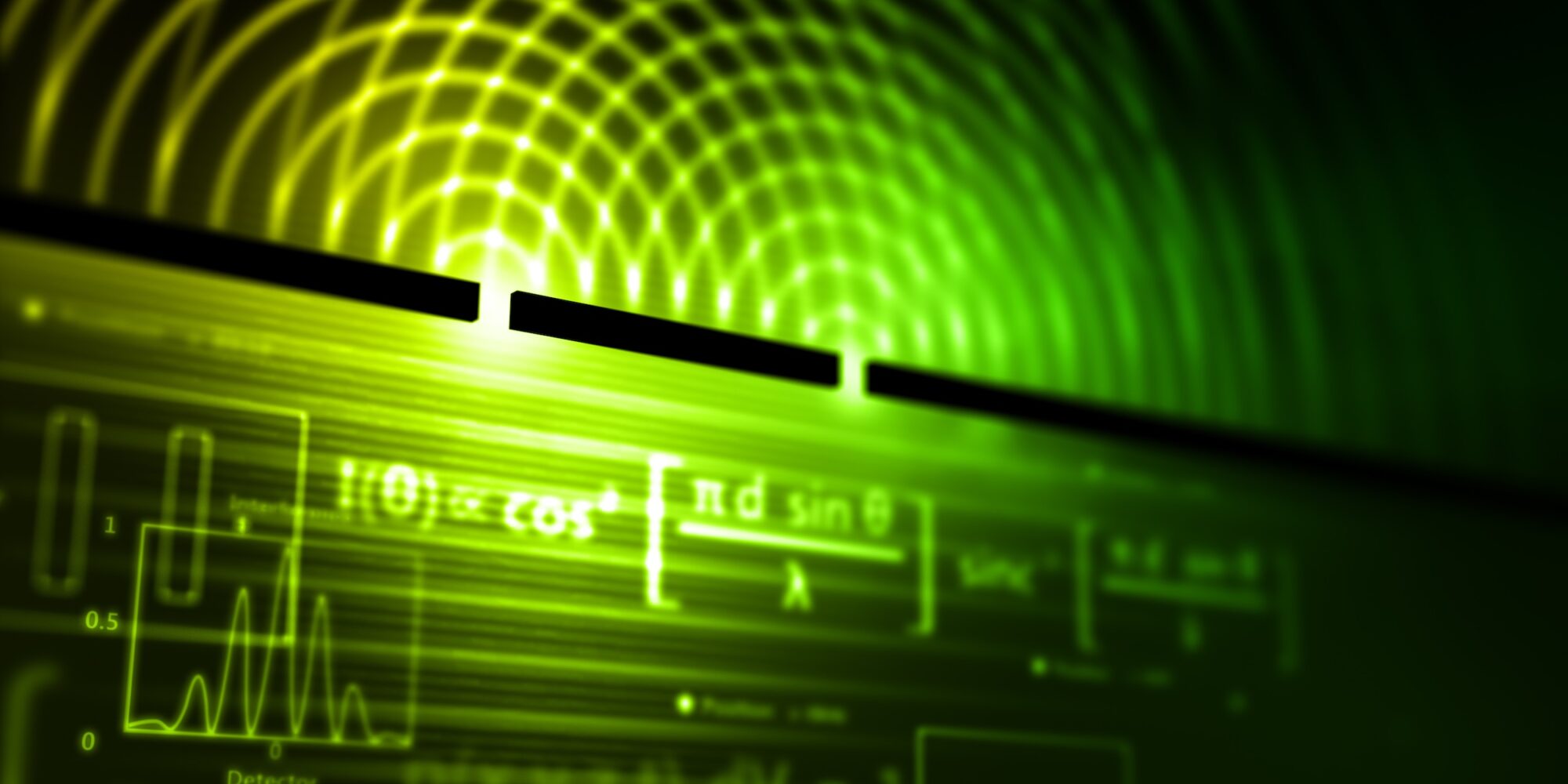

This is still a very amorphous view of the nature of reality. However, Wolfram’s work has more to say on the subject, particularly the concepts of computational equivalence and computational irreducibility, which are related. Wolfram has been able to demonstrate that there is a class of very simple programs that generate truly complex behavior—behavior that cannot be predicted with any formula and can only be determined by running the program in full. For this reason, we can say that the patterns generated by such programs are computationally irreducible. This means that, once we have the ruliad, the next step is to trim it down to the most ‘interesting’ parts—i.e., the computationally-irreducible patterns. Wolfram also demonstrates that all such complexity-generating programs are essentially equivalent in terms of the complexity of the patterns they generate. This means that we can focus on any one of these complexity-generating programs and expect to get comparable insights as with any other.

Furthermore, Wolfram and his team were able to demonstrate that these programs are able to generate high-level patterns that correspond, in certain ways, to both quantum mechanics and general relativity. So we can hypothesize that physical reality is just a high-level construct of one such a program being run at a much lower level of reality. This provides huge insight into the nature of emergent phenomena by demonstrating that a trivial program, when run long enough, can produce patterns that seem fundamentally unrelatable to it and its initial conditions (when viewed by a human observer). If we think of the world we experience as being the pattern that such a program generates, we can understand reality in terms of layers of emergence. We start with a simple program, run it until we get the foundations of physics, and then run it until we get physical reality as we know it.

Looking at the ‘timeline’ of the ‘evolution’ of reality, we start with the infinite potential that is the mind of God. Then God creates some structure—the basis for computation—and we get the ruliad. As God ‘plays around’ with the ruliad, God focuses on the programs that generate complexity. Then let’s say that God picks one and runs the program until an entire universe is generated through layers of emergence, and so we get reality as we know it.

But, as you might suspect, there’s more to the story.

Let’s talk about the concept of an observer. To Wolfram, an observer is a persisting pattern within the ruliad that can be associated with some form of identity, but is not so cohesive as to resist influence from outside of itself. So it takes in external information in the form of representations of other local sub-patterns in the ruliad. Although the pattern as a whole is irreducibly complex, there are pockets of locally-reducible sub-patterns that can be observed and represented by a model inside of an observer within the ruliad. All patterns that we, as observers, can recognize are forms of local reducibility.

Idealism has a few things to say about this interpretation. One would be to emphasize the importance of the distinction between conscious and non-councious observers. If we consider Bernardo Kastrup’s interpretation of quantum mechanics, we understand physical reality as being manifested in relation to a conscious observer. There can be non-conscious observers in the loop, such as measurement devices, but ultimately they are just part of the relationship between the conscious observer and what is being observed.

One could claim that the existence of conscious observers within the ruliad means that consciousness naturally emerges from mere computation. To an idealist, however, this rationale is reversed: consciousness is the original ontological primitive, and computation is a subset of what is possible within the activity of consciousness. So an idealist will interpret Wolfram’s work as suggesting that there are sections in the computationally-generated patterns that represent consciousness, but not that consciousness itself emerges from that pattern. The idealist understanding is that it was the God-mind that generated the pattern in the first place.

One of the implications of Wolfram’s work from a philosophical perspective is that there is a case for faith and optimism in viewing the universe as emerging from a computationally-irreducible pattern. When observing these patterns as they evolve in layers of emergence, over time they only become more complex, not less. This suggests that nature will only continue to grow and expand. There is no suggestion, in Wolfram’s work, that the universe will, for instance, ever collapse in on itself. Furthermore, it seems that every step in the evolution of the universal pattern is necessary for the emergence of higher-level patterns. If, for example, there were some apocalyptic scenario in which all humans were wiped out, that would be a step in the creation of a yet more complex reality.

Wrapped up in this discussion are the implications of computational irreducibility and the interplay between that and optimism. If we understand all of reality, including people, to be computationally-irreducible and computationally-equivalent patterns, then it follows directly that all perspectives are valid, valuable and even necessary. As with all emergence, the higher-level patterns are dependent on all the nuances of the lower-level ones. All perspectives are valid because they are God living through us, as us, and so are inherently divinely interesting.

Perhaps the most powerful concept for bridging the gap between Wolfram’s work and idealism is what Wolfram refers to as universality. Wolfram demonstrates that any of these complexity-generating programs can be set up to simulate any other one. This means that, if we find a complexity-generating program that produces the laws of physics, that program can always be reduced—in principle—to another one, by having the latter simulate the former. No matter what pattern you are looking at, there can always be a deeper pattern from which it is being generated. Computationally speaking, no pattern is then fundamental.

For the idealist, this gives insight into the nature of the relationship between individual consciousness and the patterns generated in the ruliad. We could postulate that the job of individual consciousness is to observe the patterns of reality—identifying their regularities and constraints—and then choose a lower-level pattern to reduced them to, in a manner that conforms to the observed constraints but also enables the fulfillment of other, arbitrary constraints, as determined by the conscious being. This can be understood to be the process of manifestation: from the infinite conceivable realities potentiated within the ruliad, the job of individual consciousness is to actively make choices that steer the development of the patterns of interest.

There is a sense in which this interpretation suggests that every decision made by a conscious being adds an entire new layer to the ‘bottom of the stack’ of our emergent reality. But this should not be understood literally. Although the complex patterns we observe in nature do provide deep insight into its emergent character, they are still only a representation of reality. The claim is thus not that ‘reality is a cellular automaton,’ for example; instead, the purpose of my argument is to provide some intuition for the nature of reality at a deeper level than elementary subatomic particles. My interpretation seeks to reconcile the rigid regularity of nature’s behavior that we experience—i.e., the observed ‘laws’ of nature—with the inherently creative and generative processes of consciousness.

In summary, idealism is entirely consistent with Wolfram’s findings. Furthermore, Wolfram’s work seems to go a long way in answering some of the most difficult questions for the idealist, such as ‘if all is mind, then why do things seem to follow rigid natural laws?’ and ‘why does there seem to be an objective physical reality?’ For someone entrenched in the popular physicalist metaphysics, the goal of this argument is to show that all of physical reality can be explained within the possibility space of the ruliad, which can ultimately be embedded in a universal mind.